Kim Corrall

What is a sense of “belonging” to a place? Where does it come from? Does it naturally arise as we grow up or spend time in a place, or can it be consciously developed? I had never really contemplated any of those questions until I moved to the desert some 20 odd years ago. Growing up in the northeast of the US, I felt at home outdoors. I was familiar with the plants and the rolling terrain, the smell of salt spray on the air, the depths of the fog that rolled in of an evening, and the endless green of the trees before they burst into fall color and bathed the landscape in fiery hues of red, orange, and yellow. Even spending nine years in Germany did nothing to diminish my outdoor connection. The climate and seasons were similar, the plants close enough relatives of the ones back home that it never occurred to me that I could be outdoors somewhere and NOT feel at home.

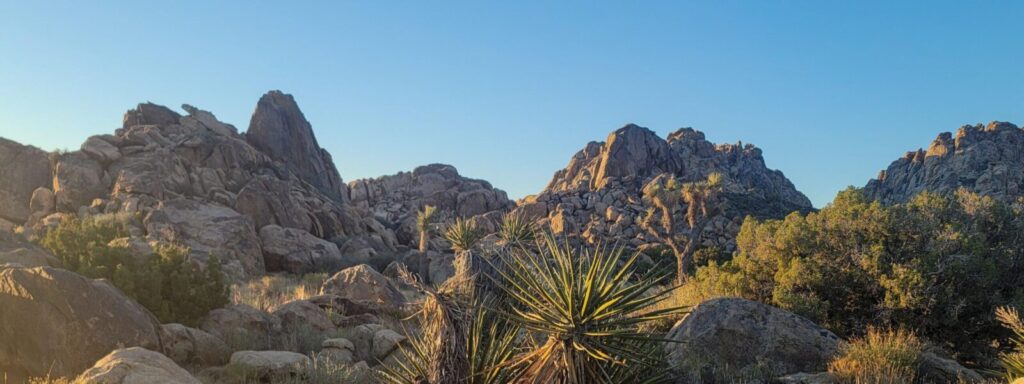

All that changed when I moved to the desert. Suddenly, I felt disoriented and out of place. The mountains were jagged and bare, the plants were unrecognizable and often seemed half dead, the seasons were undiscernible to me, and the dry winds left a layer of fine sand on every surface of my home. Rationally, I could appreciate the beauty of the rugged landscape and understand that many people found it special or even sacred, but I had no access point. As Belden Lane described it in Landscapes of the Sacred, I could tred upon the sacred space of the desert, but not enter it.

At the time I was studying herbalism and wanted to learn to forage for wild plants. Outfitted with my little basket and pruning shears, I set off to do just that”¦and realized that I could not identify a single plant in the wilds around my house. Feeling dejected, I decided I needed to find a way to learn more about this new environment. My search led me to the Field Botany and Field Ecology certificates that were being offered by UCR Extension at the time – little did I know how much they would affect the course of my life.

When I first arrived in the desert I was in the middle of a divorce – on my own with a toddler. I felt vulnerable and bruised. As I learned more about desert life, I became fascinated with its incredible resilience ““ the creosote that space themselves evenly because they can pump water at 200psi, leaving no excess for the competition; the fan palms that can get knocked over in a flood and then bend their trunks to start growing upwards again; the pocket mice who use water so efficiently that they get all they need from seeds and produce almost no urine; and the wildflowers, whose seeds can lay dormant for decades until just the right conditions prompt them to burst forth and carpet the landscape with color. I felt a kinship with these beings ““ they had a tenacity and a zest for life that I needed at the time, and I learned to love them fiercely. I also began to love the wide-open spaces and the beauty of the brilliant blue skies and chiseled mountains. Like Edward Abbey in Desert Solitaire, I found that “the strangeness and wonder of existence are emphasized here, in the desert, by the comparative sparseness of the flora and fauna: life not crowded upon life as in other places but scattered abroad in sparseness and simplicity.”

Ultimately, I created a sense of belonging to this strange land I had come to and, through that process, I grew and changed. Belden Lane states that “personal identity is fixed for us by the feel of our own bodies, the naming of places we occupy, and the environmental objects that beset our landscape.” I find, though, that personal identity is a fluid thing, extending and branching as I live my life and experience its ups and downs. I still love to visit the ocean and the forests and soak in the sound of the waves and the rustle of wind in the leaves. And, just as much now, I love to hike out into the desert expanse and discover a new rock formation or a blooming Ocotillo or sit out on a dark night to gaze up at the endless stars. My desire to ‘re-place’ myself and belong to the desert ultimately led me to my ongoing exploration of ecology, sustainability, permaculture and sacred geography. As I’ve traveled that path, my sense of place has both deepened into the desert landscape I call home and expanded outwards to the planet as a whole. For that, I am grateful.

What is your relationship to the desert? What do you love about it? Where do you feel at home? Feel free to comment below!

Though UCR no longer offers the certificates mentioned in this article, they do offer the equally wonderful California Naturalist and California Climate Steward certificates. You can find more information at UC Environmental Stewards – UCR Palm Desert